Deleted Notes & Queries response: Why do we eat pudding last?

|

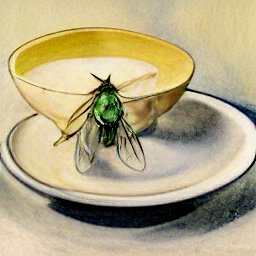

| image generated by Craiyon |

The comment has since been deleted from the website.

This blog is obviously not affiliated with The Guardian. Its reference to a question that appeared in Notes & Queries is presented under the terms of fair use.

~

Why do we eat pudding last?

As a young girl, my grandmother, along with her mother and father, her four brothers, a St Bernard who monopolised the hearth during the winter, and an African grey parrot named Joey, all occupied a cramped bungalow, that was situated towards the end of an unmade road, in Thundersley.The road remained unpaved until the late 1990s, by which time the house had long been demolished, and many of its former occupants had been interred in the terraced churchyard at St Mary's, a couple of residential streets away. Periodically, I am called upon by the church to attend to family gravestones that have become unanchored from their foundations and have slid down the hill.

The family persisted in an abiding state of finger-gnawing poverty. Puddings were reserved, not for the end of meals, but for the end of the year, when the hedgerows in the area produced the so-called 'free' or 'common' crops of berries that were required to make Heagraw Pudding (pronounced 'Hee-graw') – a dessert that evolved throughout the Autumn as different fruits came into season, and which my grandmother recalls was sometimes eaten as a main meal, when the household budget would not stretch to meat. The best berries, she informed me, were to be found adjacent to 'The Devil's Steps' – a source of local folklore. In recent times it has fallen under the scrutiny of health and safety, and is now an ivy-swamped concrete staircase, descending a steep wooded embankment, bordered on either side by a sturdy handrail. When I visited I could find no fruit bearing plants of any kind. The devil also, was conspicuous in his absence.

Given the importance of the pudding in the lives of my grandmother and her family, it came as something of a surprise to learn that it has not been widely consumed in the UK for well over a century. The dessert is better known as a speciality of New England, in the United States, where it appears on the menus of Bed & Breakfasts as Fall Souffle, though it is actually a very light, streamed sponge pudding.

The only person in my grandmother's household to consume a sweetened dessert at any other time of year was her father, who was an agricultural labourer. Every morning he would breakfast upon a saucer of sticky condensed milk that would sweeten his sweat, narcotising the field flies that were thought to spread sleeping sickness, before they were able to bite him.

A few miles south of the fields where my great grandfather toiled for most of his life, and which have now been covered up by homes, there once grew the makings of another seasonal dessert: Shad corn is a freshwater cereal crop, native to northern Europe. There is evidence to suggest that it was farmed by the ancient Britons, who modified stretches of running water, broadening channels while lessoning the depth to create 'fields'. Traces of shad corn paddies located many miles from rivers, and dating to the pre-Roman period, have been uncovered in the archaeological record. It is unclear how these inundated areas of arable land would have functioned, since the crop requires flowing water to stimulate growth and seed dispersal.

In the medieval era, shad corn was consumed voraciously by shoals of herring, who spread the seeds along their migration routes. Recently it has become fashionable in culinary circles and is sometimes served as a side-dish, as an alternative to bulgur wheat. It is the main ingredient in a milk-based dessert, sweetened with tree sap, called Avonwash Pudding, that dates to the 13th century. In the topsy-turvy world of medieval Britain, this was presented prior to the meat course. An updated version of the dessert was submitted as one of the dishes for the recent Platinum Jubilee celebrations, though it failed to make the final selection.

All four of my grandmother's brothers fought in different theatres during the Second World War. They each returned home physically unscathed, but changed by their experiences. All four of them went on to lead long, mostly happy lives.

During the war, Paul was a tank operator. A mainstay of his rations were the pots of Lionel's Apricot Jam – the only sweet thing that was routinely offered to the men in his brigade, and yet it could only be consumed after the order had been given by a commanding officer, which was usually at the conclusion of an offensive. When the fighting was fierce, the jam was repurposed to create 'jelly chargers - improvised power cells that would become active when exposed to heat (sunlight was best) and that could be used to recharge the batteries in vehicles and equipment. When the shop-soiled jam was doled out to the men at the end of an operation, it had acquired a strong metallic taste as a result of the electrodes that had been placed within it. It was nonetheless both enjoyed and appreciated.

After the war, Lionel's rebranded as 'Chargers Jam' bedecking their jars with patriotic, militaristic livery. I am told that Paul would often eat it in sandwiches in place of a dessert. He claimed that he missed the metallic taste and even made attempts to recreate the lost flavour himself by placing strips of copper inside the jars. He died in 1987, a year before the Chargers factory in Poplar closed down.

I hope this is of help.

|

| image generated by Craiyon |

Comments

Post a Comment