Deleted Notes & Queries response: Which sport is the most difficult to master?

|

| image generated by Craiyon |

The comment has since been deleted from the website.

This blog is obviously not affiliated with The Guardian. Its reference to a question that appeared in Notes & Queries is presented under the terms of fair use.

~

My Christmas present from Ethel Luff (a mug bearing the image of a kitten entangled it's own unravelled DNA code) arrived garnished with a section of Olympic-grade gymnastic ribbon.

“I'm retiring” she announced, when we spoke in person a couple of months later, though she used a stronger turn of phrase. “Well, I retired over two decades ago, but now, if anyone asks me for a demonstration, I can say with all honesty that I no longer have the equipment. No more pushing the settees up against the wall and prancing around on the shagpile, with all my bits flopping about, for the benefit of the magpie-eyed Hampstead intelligentsia. I've ended up in too many novels about the jaded upper middle-classes that way. I am drawing a line under that chapter of my life.”

If Luff were to draw an actual line, it would be the most interesting line you had ever seen, and would leave you scratching your head for days, as you attempted to grapple with its universal significance.

Regardless of whether she ever takes up the ribbon again, she remains both a champion and a pioneer of Vanguard Waveform Gymnastics – a sport that requires a deep understanding of wave-particle physics, along with unique insights into theoretical wave patterns, and the physical grace to channel these concepts through two thin bands of 6-8m long, polarised satin, as part of a floor routine.

“Physical grace is not a trait one sees a lot of among people working in the theoretical sciences,” says Luff. “My mother was a ballet dancer. Consequently, I was a dancer from a very young age, so it came naturally to me.”

The floor routines are graded according to their accuracy in recreating the proposed waveforms, and by how far they advance of our understanding of the processes they describe, and broaden our knowledge of the universe. It can take several months to determine a winner of a competition (the record is 19 months) as each performance is subjected to peer review; rigorously tested on a theoretical level and forensically dissembled to root out plagiarism.

“Having a competent team of board-scribblers backing you up in the aftermath of a competition is essential,” claims Luff. “It's a team sport with a massive logistical and support component. In my time I have seen some very mediocre routines end up scoring highly because the backroom element were competent enough to bolster the theory underlying the performance and extrapolate fresh insights from it. Conversely, I have seen some routines, that were transcendent on the day, founder because the person waggling the ribbons overreached, and their support crew couldn't make their concepts hold up.”

It is these impracticalities that have, thus far, stymied Vanguard Waveform Gymnastics' inclusion in the Olympic Games. While advances in A.I., that allow performances to be assessed on the same day, may pave the way forward, there are other hurdles to field:

“It's unsightly to watch,” admits Luff. “There's no getting around it. At the theoretical end of waveform physics things get jarring and decidedly avant-garde. My husband describes my dancing as like watching someone juggle shards of glass.”

Currently, most waveform gymnastic competitions occur under the incongruous umbrella of physics conferences, with the most prestigious event being held as part of the award ceremony for the Nobel Prize for Physics (the result of these competitions are announced the following year).

“There is a dream of convergence,” says Luff. “That someone's Stockholm routine will expose a heretofore undiscovered universal concept that is so profound it will end up snagging them the Nobel Prize.”

“What makes a good Vanguard Waveform Gymnast?”

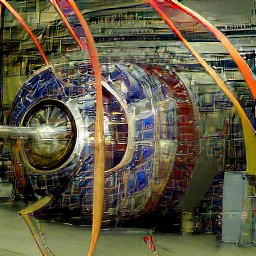

“The suppleness of a young body combined with the experience-based instincts and capacity for critical thinking of an old soul. So a unicorn, essentially. I was asked to teach VWG classes for the staff at the Large. Hadron Collider. They thought that it might help to move along some of the work being done there. I wasn't about to up-sticks to Geneva at my age, no way.”

As Luff makes her delayed exit from the mat, the wunderkind of West Horndon, Margaret Mcminn, is preparing to enter the sport, aged just 15. When I first meet her, she is bemoaning the 8 metre restriction on ribbon length in performances:

“I think we could do so much more to deepen our understanding of concepts if ribbons were extended beyond the 10m range,” she says. “It's vexing because I am closing in on my peak as a physical performer and there is something about being in competition that really kicks the mind into gear. When I am on the mat I am always developing new angles of approach. I am like a giant squid using its two main tentacles to feel out its surroundings in the black depths.

At this point Mcminn's mother, Heather, puts her head around the door.

“Has she told you how she thinks she's a squid?” she enquires.

“I love my mother, but she doesn't understand what I am doing,” says Mcminn quietly.

I hope this is of help.

|

| image generated by Craiyon |

Comments

Post a Comment