The sands miscalled it

We (that is Neale

Venise and myself) had been trying to work out what had changed in

the Ténéré – an area of sandy plains located in northern-central

Sahara desert. It is within the shifting topography of this desolate

region that immense storms, manifesting as curtain walls of roiling

dust hundreds of feet high, lay down their foundations. Once they

grow beyond a certain critical mass they untether themselves and

advance approximately westwards at a walking pace, until they hit the

coast, at which point they deviate north or south, entering the

subtropical zones as windless monsoons that leave incongruous dunes

in their wake.

These storms are slow

to germinate, usually building to a peak over several months. Their

roots lie in the electrical charge that is generated by sand

particles moving against each other. These currents form meandering

v-shaped channels in the sand that can stretch for thousands of

miles. Typically when a gathering storm decamps it will remain close

to the ground and follow the electro-magnetic charge along the most

pronounced of these troughs. This makes it easy to determine the

pathway of a storm, and to either take avoiding action or temporarily

evacuate any affected settlements.

Predicting the course

of a storm used to entail placing sentries on high ground where they

could establish a pseudo bird's-eye view of the surrounding land. The

nomadic Sagembu were reputedly able to train ravens for this purpose.

These days, predictive measurements are taken by satellite.

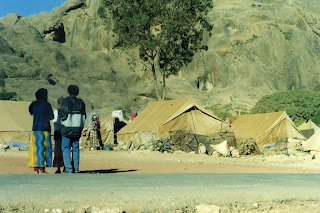

Since 2019, more storms

have been observed deviating from their established courses and

lifting off into the heavens, only to descend from the otherwise

clear blue sky days later, like sudden ambushes, scattering tents and

tearing down mud brick buildings, before rising once more, leaving

behind an eerie stillness.

Neale and myself

witnessed a small storm detach from its expected pathway and rear off

at a slant, like a derailing locomotive. We believe that a storm's

separation from its electromagnetic root system causes it to become

susceptible to localised forces outside of those that generated it,

and thereafter wildly unpredictable.

Beyond that hypothesis,

we were never able to make any sense of it. Inconveniently, a few

hours after our arrival in Tahoua, I fell down the stairs at the

hotel and broke my right foot. There was no doctor available and I

was forced to rely on the ministrations of a local pharmacist. Of

course, Neale had to do all the driving, which was often difficult.

He had brought his

seven-year-old son, Graham's, fridge magnet collection with him to

“supercharge” along one of the storm lines. He put them down on

the ground for no more than a minute, while we took some

topographical readings. When he turned around to retrieve them, they

were gone, engulfed by the sands. We could never find them.

Graham is autistic and

was devastated by the loss of his magnets. It was the cause of an

enormous row between himself and his wife Fiona. I believe they even

separated for a while.

As if that wasn't

enough, Jack Sibson had returned to the Unified Wells & Aquifers

Company, following his exile in Germany. Predictably things went very

much as they had done before. Neale took Jack's side, which I think

he would agree in hindsight was a mistake. It put a distance between

the pair of us that neither of us was able to cross. Neale is retired

now and I wouldn't know how to contact him directly. For reasons I

will not go into, I have been on permanent sick leave since 2015.

Afterword

There is a eBook available, existing in the same world as what you have read above, and tenuously related to it:

The Missionary Dune - Sam Redlark

Comments

Post a Comment